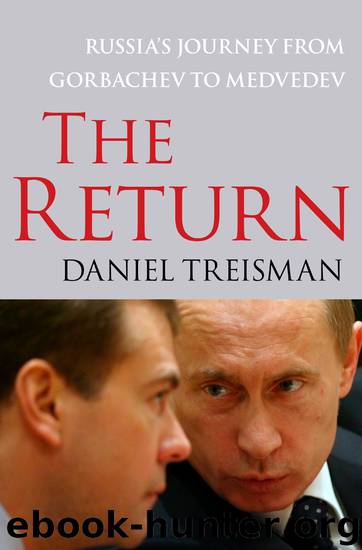

The Return by Daniel Treisman

Author:Daniel Treisman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Free Press

Russia’s Ethnic Revival

Before returning to the war, it is worth considering the context in which it occurred. With its vast size, its history of migrations and conquests, Russia contains a myriad of small ethnic groups—from the reindeer-herding Chukots and the shamanistic Nentsy to the Muslim Avars and the throat-singing Tuvans. The 1989 Russian census identified 105 nationalities with more than one thousand members. Ethnic Russians dominated, with 81.5 percent of the population, followed by Tatars (3.8 percent), Ukrainians (3.0 percent), Chuvash (1.2 percent), and Bashkirs (0.9 percent). The Chechens, with 899,000 members in 1989, came in eighth.

Designing Russia’s administrative architecture, Stalin gave the largest non-Slavic ethnic groups their own “autonomous republics.” By 1992, after the Chechen-Ingush split, there were twenty-one of these. On paper, the republics had broader rights than the country’s other sixty-eight regions. They were entitled to their own constitutions and official languages; their heads of government served ex officio in the Russian government; and their borders could not be changed without their governments’ consent. Eight republics, clustered in the Northern Caucasus and along the Volga River, were traditionally Muslim (Adygeya, Karachayevo-Cherkessia, Kabardino-Balkaria, Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Tatarstan, and Bashkortostan). Another three (Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva) were historically Buddhist.

The other sixty-eight regions broke down into several categories. First, there were forty-nine oblasts, or provinces, and six krays, or territories—categories that in practice had the same status and rights. The only difference was that krays might contain sparsely populated autonomous okrugs, or districts, of which there were ten in 1992. Although named in honor of smaller non-Russian ethnicities, the autonomous okrugs had no additional rights and were subordinate to both the federal government and the surrounding kray. The two federal cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg had the same status as oblasts and krays. Finally, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, on the border with Chinese Heilongjiang, existed to prove that Stalin’s Soviet Union did not engage in anti-Semitism. Located in one of the swampiest corners of the Far East, it was inhabited mostly by non-Jewish ethnic Russians.

As glasnost dissolved previous inhibitions, a gale of nationalism seemed to sweep in from Eastern Europe and the Baltics. From Karelia on the Finnish border to Sakha in Eastern Siberia, leaders of autonomous republics began demanding new cultural and political rights, adopting their own constitutions, anthems, and flags, asserting the superiority of their laws over federal ones, even declaring themselves sovereign states. Checheno-Ingushetia’s sovereignty declaration actually came quite late; it was the fourteenth republic within Russia to make one. Some nationalists called for changes in borders. In southern Siberia, a Buryat party agitated to unite Russian Buryatia with Mongolia, while some Altays and Khakass dreamed of a Turkic Siberian Republic. In Tatarstan, nationalists quite seriously demanded that Moscow begin “peace negotiations” to end the “state of war” that had existed since Ivan the Terrible sacked the capital Kazan in 1552. In March 1992, in a referendum called by the Tatar government, 61 percent of voters endorsed the republic’s assertion of sovereignty. Moscow is said to have moved troops up to the republic’s border.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18993)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12175)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8870)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6854)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6243)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5759)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5706)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5479)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5408)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5196)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5127)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5065)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4898)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4757)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4724)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4677)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4484)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4472)